How John Law Enriched Your Vocabulary and Bankrupted Everything Else

March 21, 1729: Hell Gets a Chief Financial Officer

Wall Street did not pioneer the stock market crash. No, that distinction belongs to France some 70 years before there was a New York Stock Exchange. Yet, in a way the Crash of 1720 was America’s fault. All those French investors were absolutely certain that there were gold mines in Louisiana, and that fortune was just waiting for them. They had been assured of it by that widely-acknowledged financial genius John Law.

Wall Street did not pioneer the stock market crash. No, that distinction belongs to France some 70 years before there was a New York Stock Exchange. Yet, in a way the Crash of 1720 was America’s fault. All those French investors were absolutely certain that there were gold mines in Louisiana, and that fortune was just waiting for them. They had been assured of it by that widely-acknowledged financial genius John Law.

An economist by education, Law (1671-1729) actually earned his livelihood as a gambler; he may have been the pioneer of card-counting. Law also was a convicted murderer; but since it involved a duel over a woman, the French only esteemed him the more. The charismatic Scotsman managed to ingratiate himself with the Duke of Orleans and ended up as the comptroller of the French currency.

In that position, Law introduced the use of paper money in France. The logic of the innovation was impeccable; paper money was easier to handle than bulky bullion and so would facilitate business. Of course, the paper money had to represent legitimate value and be redeemable for a guaranteed amount of gold or silver. However, the French government did not understand that specific principle; the printing presses of the Royal Mint produced reams of increasingly devalued paper.The notes were soon worth one-fifth of their face value.

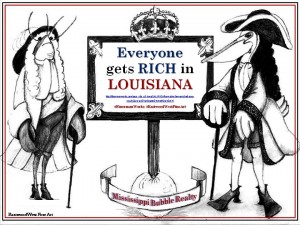

But Law thought of a remedy for this: offering stock shares whose potential profits would more than compensate for the depreciating currency. At the time France claimed a vast tract of land in North America, stretching from the Gulf of Mexico to Canada: 828,000 square miles we know as the Louisiana Territory. Law persuaded the French government to grant him the exclusive mining and trading rights to the territory. In so vast a territory, there had to be gold and silver mines. Mexico had them, and the Louisiana Territory was almost next door. The professional gambler thought he was playing the odds, and he managed to convince the French investors of a sure thing. They would be fools not to invest in his venture, Compagnie d’Occident.

Their buying became a frenzy; the company’s shares went from 500 Livres in 1719 to 18,000 Livres in 1720. Besides, as the French investors knew, their money was worthless so why not gamble with it. The shares of Law’s company seemed preferable to the inflated currency. However, even if Louisiana had gold mines, the price of the stock had become ridiculous. And the tottering French economy would certainly not be saved by what Louisiana really had to offer: crawfish.

The stock collapsed before the year was over, dropping to 300 Livres. Bankrupt himself, Law found it wise to leave France. Despite his notoriety–or because of it–he had no trouble finding sanctuary. Any man who had done that much harm to France was always welcome in Britain. (And in his flush days, Law had “secured” a pardon for that murder charge.) Law resumed his career as a gambler but could not resume his good luck; he died in threadbare circumstances on this day in 1729.

The French monarchy itself had lost part of the Treasury in the market crash and would never regain solvency. Of course, it would continue to spend money as if Louisiana were made of gold. (The monarchy’s IOUs finally came due in 1789.) Historians refer to this scandal as the Mississippi Bubble.

Ironically, while the stock price was surging, the investors thought that they were rich–if only on paper. A term was coined to define the extent of their new wealth: millionaire.

I think I’ve seen Mississippi Bubble in the candy aisle at Target.