Idiot Brothers-in-Law of History

January 8, 1815: The Battle of New Orleans

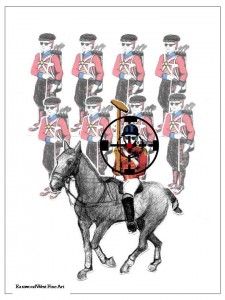

On this day in 1815, Edward Pakenham’s watch must have been running fast. The British general evidently thought it was 1915 and that he had to slaughter his troops in as stupid a manner as possible. So, he ordered a full-frontal assault on the entrenched American positions at New Orleans. Andrew Jackson’s troops did not have machine guns but they certainly knew how to make the best use of their Kentucky long rifles . Men who can shoot a squirrel out of a tree are not likely to miss a prancing brigade in red coats.

On this day in 1815, Edward Pakenham’s watch must have been running fast. The British general evidently thought it was 1915 and that he had to slaughter his troops in as stupid a manner as possible. So, he ordered a full-frontal assault on the entrenched American positions at New Orleans. Andrew Jackson’s troops did not have machine guns but they certainly knew how to make the best use of their Kentucky long rifles . Men who can shoot a squirrel out of a tree are not likely to miss a prancing brigade in red coats.

Edward Pakenham was the brother-in-law of the Duke Wellington and actually had proved himself to be a brave and effective subordinate in the Peninsular Wars. In fact, Pakenham was leading the same troops who had performed so brilliantly in Spain, defeating larger French forces. At New Orleans, the British troops for once had the numerical advantage; they outnumbered the Americans by two-to-one. Perhaps that is why Pakenham did not bother with tactics.

The American forces did have an abysmal reputation. In 1812, they had a forty-to-one numerical advantage over the 5000 British troops in Canada; and guess who was winning? American attacks on Canada sometimes never got past the border. Worse, those borders were shortening. The territories of Maine, Wisconsin, Illinois and Michigan seemed more likely to become provinces than states. America’s best hope was the military genius of its ally Napoleon, and 1812 proved poor timing for that alliance. By 1814, Napoleon had retired to Elba, and now Britain could turn its full and vindictive attention to America. The Duke of Wellington was offered the command the punitive expedition. Perhaps Ontario was less alluring than Paris and Vienna; compared to Napoleon, James Madison was certainly anti-climactic. Wellington declined the commission and even recommended a peace settlement. Nonetheless, he did have a brother-in-law to spare.

The British had no real military objective; they simply wanted to make the Americans miserable. Burning Washington certainly accomplished that. Seizing the rich port city of New Orleans would be another humiliation. The city seemed vulnerable, with only a meager slapdash force to defend it. Pakenham assumed that his veterans would simply push the Americans aside. That was a mistake he did not live to regret; neither did a quarter of his command.

To add irony to the disaster, the battle was unnecessary. The War was over; however, the news of the Treaty of Ghent had yet to reach the opposing armies at New Orleans. Of course, the Battle of New Orleans might have taught the British military the disadvantages of a frontal assault. However, judging from the number of British War Memorials, commemorating 1914-18, that lesson was not in the syllabus at Sandhurst.