Veterans’ Day at the Movies

Posted in General, On This Day on November 11th, 2014 by Eugene Finerman – 4 CommentsNovember 11, 1918: Western Civilization gave itself a slight respite from self-destruction.

The Armistice lasted 20 years, allowing sufficient time for the toddlers of 1918 to grow into their boots and helmets. (And during that respite, corporals and sergeants promoted themselves to Fuhrers and Duces.)

The Armistice lasted 20 years, allowing sufficient time for the toddlers of 1918 to grow into their boots and helmets. (And during that respite, corporals and sergeants promoted themselves to Fuhrers and Duces.)

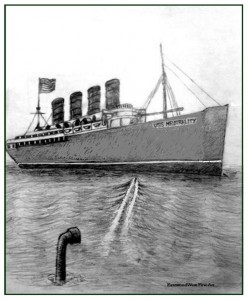

We Americans did actually win the First World War simply because we still had a breathing generation of draft age men and we showed up in France at the right moment. Had the Chinese sent one million men to France in 1918, they could have won the war, too. Timing is everything.

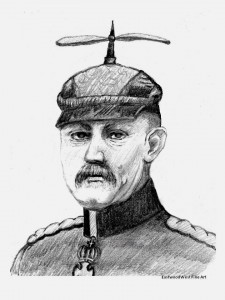

America was barely involved in World War I. We entered the War in 1917, missing all the excitement of Gallipoli, the Somme and Verdun. More doughboys died from influenza than Krupp munitions. Our chief casualties may have been Mary Pickford and Lillian Gish, who were constantly escaping “a fate worse than death” from the Hunnish clutches (or whatever the pertinent organ) of Erich von Stroheim in Hollywood’s depictions of the War. (It should be noted that in her long film career Miss Gish was also nearly raped during the French Revolution and the American Civil War.) Given our limited participation in the Great War, we commemorate November 11 as a catch-all day for all of our Veterans.

However if you really want to honor the veterans of the most futile war in history, you can do so any day on Turner Classic Movies. Just turn on a film from the Golden Age of Hollywood and look at the British actors. To a man, they served in a far more harrowing theater than all the terrors of working with Bette Davis. Many of them were left scarred. Herbert Marshall had the unique distinction of being a leading man with a wooden leg. Claude Raines was blind in one eye. When you see Ronald Colman’s fencing in “The Prisoner of Zenda” you wouldn’t know that he had a kneecap shot off. Lieutenant Nigel Bruce was machine-gunned in the buttocks; that is not the kind of wound that gets the Victoria Cross. If Leslie Howard seemed introspective and other-worldly, shellshock can do that. In fact, to save time, let me recite the British actors who somehow avoided being maimed in France. Well, Leo G. Carroll was wounded in the Middle East; at least, he had that originality.

The most veteran of the British veterans was Donald Crisp, the kindly father figure in so many films of the Thirties and Forties. (He did have an incestuous interest in Lillian Gish in “Broken Blossoms”; but you know, I am starting to have my suspicions about Miss Gish. Did the woman gargle pheromones?) Crisp fought in the Boer War and then served again in the Great War.

If you want to see a microcosm of British history, watch the 1940 production of “Pride and Prejudice.” The middle-aged actors–Edmund Gwenn and Melville Cooper– had served in the Great War. The younger members of the cast–Laurence Olivier and Bruce Lester–were to have their turn. The Armistice was about to end.

And Erich von Stroheim would threaten a new generation of actresses.