A Real Milestone in History

Posted in General, On This Day on September 13th, 2009 by Eugene Finerman – Be the first to commentSeptember 13th: 533: King Gelimer Picks a Bad Time to Lose His Mind

Battles do require a name. History prefers a more specific nomenclature than “Was Grant Drunk Again?” or “Those English Archers Are Really Good, Part I.” Geography usually obliges with some form of identification: the nearest town, the bordering river or, on this day in 533, a signpost. Today is the anniversary of the battle of “Ten Miles From Carthage.” It sounds more dignified in Latin, “Ad Decimum”, although neither of the armies spoke that language. One army took orders in Greek, the other in a German dialect, but the signposts of North Africa were in Latin.

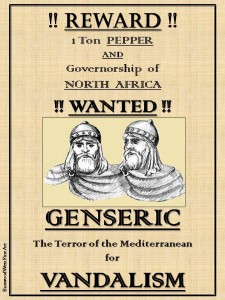

North Africa had been part of the Roman Empire for almost six centuries, the consequence of losing all those Punic Wars. In the early fifth century, however, the territory had been acquired by a group of entrepreneurs known as the Vandals. They had first migrated from Spain where they had been among the first German tourists to loot Roman Iberia. Unfortunately for the Vandals, the Visigoths also heard about Hispania and migrated there, too. Preferring to be the sole barbarians on the peninsula, the Visigoths began wiping out the Vandals. Half of the tribe was gone when the Roman governor of North Africa saved the Vandals. He was rebelling against the Emperor and needed mercenaries, so he transported the tribe to North Africa.Ironically, the Roman governor called off his rebellion, but the Vandals didn’t. They soon occupied the territory extending from Libya to Morocco. (Yes, Rommel’s Afrika Korps was actually the second German invasion there, and the less successful of the two.)

Their rule in North Africa was relatively benign. They restored the stability and prosperity that the disintegrating Roman Empire had failed to maintain. The Vandals’ most conspicuous failing was religious intolerance. Like many of the Germanic tribes, they were Christians but did not subscribe to the theological convolutions of the Nicene Creed. To the Germanic mind, God was Odin and Jesus was Thor. However, while the Goths were tolerate of the more sophisticated interpretations of Christianity, the Vandals were not. They persecuted the Church–and earned their ever-lasting infamy. (More savage tribes such as the Franks and the especially barbaric Angles and Saxons eventually converted to the Nicene Creed and received a baptism in history’s whitewash.)

The Vandal kingdom in North Africa lasted until 534. To the Vandals’ surprise, the Byzantine army had stopped cowering behind city walls and now was on the attack, intent on restoring the lost western half of the Roman Empire. The Emperor Justinian had meticulously planned the campaign, using a superior army and insidious–dare I say “Byzantine”– diplomacy to overthrow the barbarian kingdoms. He would use the Ostrogoths against the Vandals, the Franks against the Ostrogoths, the Visigoths against the Franks, and the Visigoths were always fighting among themselves. (Justinian apparently did not consider Britain worth reconquering; otherwise he would have pitted the Angles against the Saxons.) The Emperor’s Grand Scheme did not quite work because no one could rely on the Franks–and how little has changed–but it proved successful in North Africa.

To distract the Vandals and divide their forces, the Byzantines subsidized a rebellion on the northern-most possession of the kingdom, the island of Sardinia. With the Vandals’ fleet and sizable portion of their army conveniently distant, the Byzantine fleet sailed from the friendly ports of Ostrogoth-ruled Sicily and disembarked a 15,000 man army in North Africa in 533. Having forgotten Roman corruption, and not yet acquainted with Byzantine bureaucracy, the North Africans welcomed the imperial forces as liberators. The troops’ usual inclination to pillage was checked by a commander of remarkable rectitude: Belisarius. The young general had demonstrated some ability in fighting the Persians, but he had especially impressed the Emperor by massacring rioters in Constantinople. Now he was to defeat an army of 30,000 and overthrow the Vandals’ kingdom.

Marching to Carthage, the capital of North Africa, the Byzantines were ten ten miles from the city when they found the Vandal army in the way. The Vandals’ King Gelimer had an excellent plan for the battle; he would outflank and envelop the invaders. Of course, such manuevers do require some coordination; otherwise you are simply fragmenting your forces in front of the enemy. Guess what happened. The Vandal troops that were so supposed to block the Byzantines arrived in installments, and that is how the Byzantines slaughtered them. Among the casualties was Gelimer’s brother. Then the Vandals’ flank attack began–but without any support from the no longer living vanguard or the yet- to-arrive main force under Gelimer. Worse, they ran into Belisarius’ Hun mercenaries–who did not believe in taking prisoners.

Gelimer finally showed up on the battlefield and his fresh, larger force seemed to be gaining the advantage over the Byzantines; but then the king found the body of his brother and had an emotional collapse. In the midst of a battle, he insisted on his brother’s burial. This was definitely the wrong time for Vandal sensitivity. Belisarius did not wait for all five stages of Gelimer’s grief to rally the Byzantines and counterattack. The disoriented Gelimer even led his retreating troops in the wrong direction, not back to Carthage but into the desert. The gates of Carthage were opened to the Byzantines, and Belisarius would enjoy a dinner that had been prepared for Gelimer.

The refugee king did attempt to rally his forces but never quite succeeded in reviving his sanity. For a man who had killed his cousin for the throne, Gelimer really was too sentimental for the job. He was finally captured in 535 and presented as a trophy to the Emperor Justinian. Gelimer sang dirges to himself and had an inexplicable, disconcerting laugh. He was allowed to live the rest of his fragile life in a peaceful retreat. Belisarius was on his way to Italy, and in a few years he would be presenting another but reasonably sane king to Justinian.

As for the Vandals, they evidently made some impression on the natives of North Africa. The blond hair and a possible tendency to goosestep would seem conspicuous. Almost two centuries later, when those North Africans conquered Spain, they remembered that the Vandals had come from there. So the Moors referred to this realm as “Andalusia”.