The Tsar’s Shaving Grace

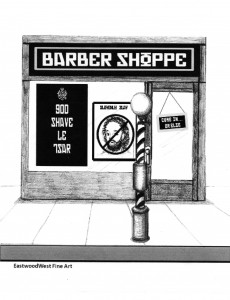

Posted in General, On This Day on September 5th, 2009 by Eugene Finerman – Be the first to commentSeptember 5, 1698: Peter the Great Imposes a Beard Tax

Peter t he Great had inherited a medieval empire. Unfortunately, the 17th century really was an inopportune time to be medieval. Even Spain was only a century behind the times. The young Tsar was determined to modernize Russia, and he wanted to see western progress for himself. So, in 1697, he travelled “in cognito” through Germany, France, the Netherlands, and Britain. Peter was not as “in cognito” as he hoped, being 6’7″ and traveling with a large entourage. The King of England did not normally greet every tourist. And most tourists ask for fresh towels rather than an alliance against the Ottoman Empire. Nonetheless, Peter found the experience to be edifying and he returned home with plans to impose progress on Russia.

he Great had inherited a medieval empire. Unfortunately, the 17th century really was an inopportune time to be medieval. Even Spain was only a century behind the times. The young Tsar was determined to modernize Russia, and he wanted to see western progress for himself. So, in 1697, he travelled “in cognito” through Germany, France, the Netherlands, and Britain. Peter was not as “in cognito” as he hoped, being 6’7″ and traveling with a large entourage. The King of England did not normally greet every tourist. And most tourists ask for fresh towels rather than an alliance against the Ottoman Empire. Nonetheless, Peter found the experience to be edifying and he returned home with plans to impose progress on Russia.

Peter would have a modern army and, for the first time in six centuries, a navy. (The last Russian fleet had been incinerated by the Byzantines.) However, modern armaments would be wasted as long as the Russian mind remained medieval. Peter was determined to modernize the society as well, starting with the aristocracy. The Russian nobility had been recycling Byzantine fashion for five centuries: retro is one thing but this was stagnation. Peter demanded that his nobles look like their peers in the west.

The ladies of the court found the new fashions immodest; in their traditional Muscovite garb, a neckline was literally a neckline. For the men of the court, the transistion was worse. In place of majestic enveloping robes, they now had to wear breeches, leaving no doubt as to the shape of their legs and anywhere else in the area. But Peter made those men feel truly naked by demanding that they shave. Russian men took great pride in their beards, but Peter regarded the look as an embarrassing anachronism. No, his subjects would be as clean-shaven as Western Europeans–or else. On this day in 1698, Peter imposed a beard tax of 100 rubles annually on every Russian male except peasants and priests. In fact, even payment was no definite protection. If Peter was in one of his zanier moods, he personally would shave his hirsute subject.

Peter’s policies and tantrums did transform the aristocracy. By the early 19th century, the nobles of St. Petersburg would have been indistinguishable from those of London. (The nobles of Paris generally could be distinguished by their lack of heads or their employment as tutors in London and St. Petersburg.) The Russian aristocracy only spoke Russian to their servants; among themselves, ils parliaent francais. Indeed, when Tsar Alexander I met Napoleon in 1807, it was noted that the Russian spoke the better French. The scholarship kid from Corsica had a thick accent and would have sounded like a French Tony Danza.

For the rest of Russian society, however, Peter’s reforms were either meaningless or just an added burden. The serfs probably had to work harder to pay for master’s western wardrobe. Peter had not addressed Russia’s injustices or brooding turbulence. He had merely transformed an isolated, backward nation into an aggressive, backward nation.