From a Russian perspective, the fight seemed fair. Outside the walls of Kiev was a besieging army of Mongols, but within Kiev there were 400 churches, all spiritually fortified with icons and relics. A miracle should have been effortless: a battalion of sword-wielding angels or at least a timely plague in the Mongol camp. The devout Russian garrison expected no less; otherwise, the outnumbered and beleaguered force should have surrendered when Mongols emissaries had demanded it.

In fact, a miracle was all that the Kievans could expect. No Russian army was coming to their relief; there was no more Russian army. The Mongols had demonstrated its customary exterminating efficiency; at least the buzzards ate well. And the Mongols would be impervious to the Russian winter. Raised in the Gobi Desert and inured to Siberia, the Mongols would have regarded December in Southern Russia as a vacation. So, the Kievans should have been reconciled to a servile surrender. Yet, they felt so confident and chipper that they murdered the Mongol diplomats.

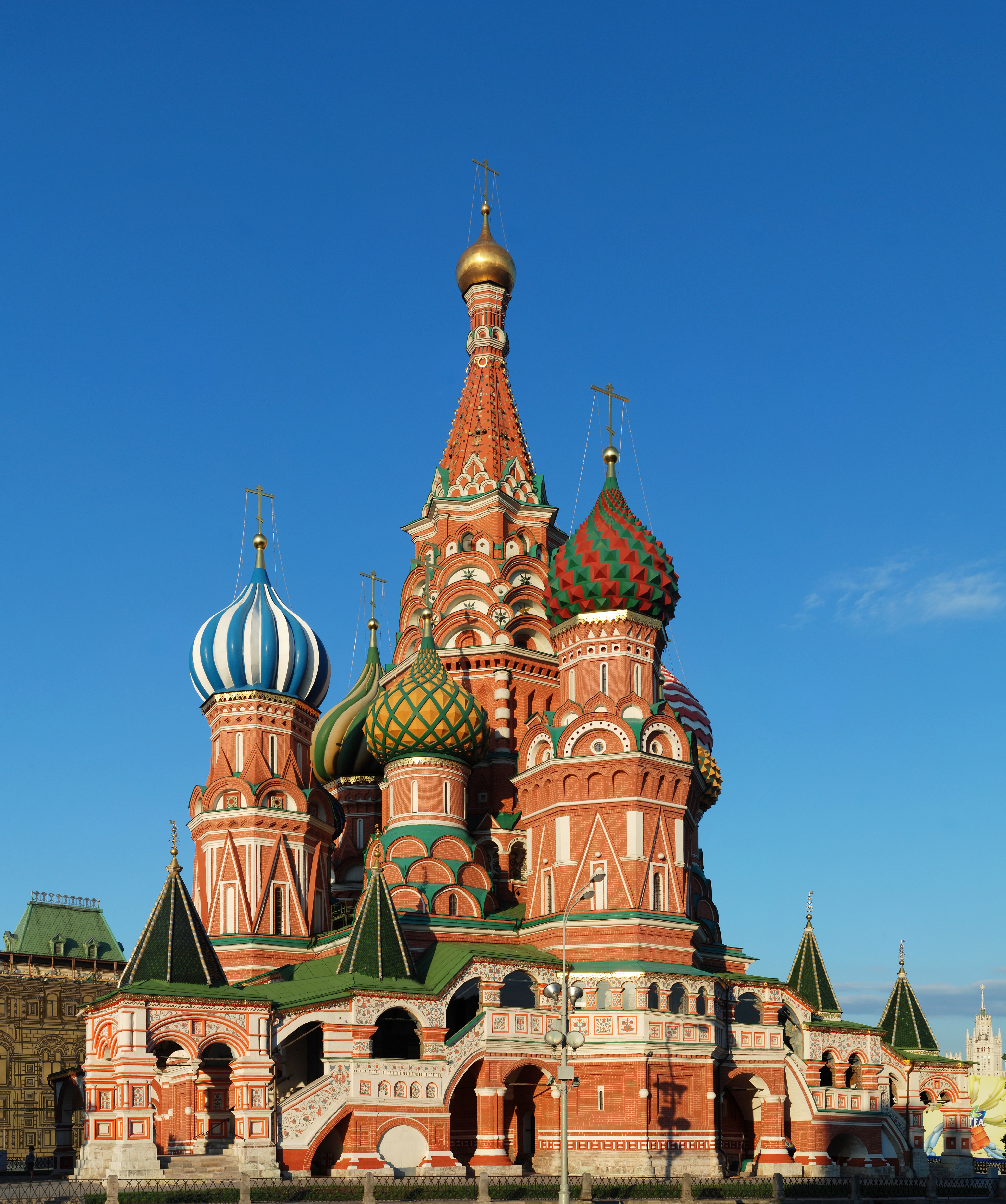

Perhaps the Mongols were supposed to be intimidated by such bad manners. They weren’t. It turns out that their manners were even worse. When they stormed Kiev, on December 6, 1240, they massacred or enslaved the population of 50,000, then leveled the city. Kiev certainly was worth looting. Check your 13th century editions of “Let’s Go Europe.” Even with a second-hand Byzantine culture, Kiev would have been richer and more sophisticated than Paris and London.

Kiev was the undisputed cultural center and tenuous political capital of feudal Russia. After the Mongols, however, Kiev would have been hard to find. In the wake of this annihilation, the remnant Russian culture shifted from its southern, Black Sea orientation to the more isolated, less devastated principalities in the North.

What had been the heartland of Kievan Russ was no longer even Russian. The Mongols settled in the south, creating a Khanate along the Black Sea. And Poland occupied the western region. Under this Polish rule and its occidental influence, a hybrid culture with a distinct identity emerged: Ukrainian.

Among the remaining Russian states, Novgorod was so far in the northwest that the Mongols never reached it. (Out of prudence, the city still paid tribute to the Khan.) Its safe distance from the Mongols, however, also made it ominously close to the Swedes and the Germans. (This might make a good Eisenstein film.) But when it wasn’t fighting for its survival, Novgorod was willing to trade with the West.

And then there was Moscovy, battered but standing, isolated, brooding, plotting and waiting. Any resemblance between its policy and the Russian character may not be a coincidence.