Urban Renewal, Byzantine Style

Posted in General, On This Day on January 13th, 2010 by Eugene Finerman – 2 CommentsJanuary 13, 532: Green and Blue Clash With Purple

On this day in 532 the citizens of Constantinople protested against a corrupt and tax-loving government by burning down half of their city. The rioters displayed a remarkable unity; they were composed of two political factions–the Greens and the Blues–who usually hated each other. These two parties had evolved from the fans of two competing chariot racing stables; green and blue were the identifying colors of the respective teams.

On this day in 532 the citizens of Constantinople protested against a corrupt and tax-loving government by burning down half of their city. The rioters displayed a remarkable unity; they were composed of two political factions–the Greens and the Blues–who usually hated each other. These two parties had evolved from the fans of two competing chariot racing stables; green and blue were the identifying colors of the respective teams.

However, the Byzantine personality (Greek pedantics + Christian theology – Hellenic charm) would not be content with just rooting for a sports team. The fans organized into political parties with vying interpretations of the Trinity. Of course, each interpretation of the Trinity would have a militia to expound it. Between the Greens and the Blues, Constantinople was always on the verge of a riot; but the Imperial government was usually adroit at balancing the factions, playing one off against the other.

The Emperor Justinian should have been a master of this statecraft. He had an amused contempt for mankind and had a genius for cultivating the vices in others; he literally brought out the best in your worst. Appreciating their “talents”, Justinian would appoint thieves to be treasurers, hucksters as diplomats, and elevated an actress to empress. Yet, this wily Emperor misjudged the temper and the patience of Constantinople’s factions.

The two rivals joined forces, and they gave their alliance a name: Nika. It is the Greek word for victory. In a week of rage, half of the city was destroyed. Demonstrating their new-found ecumenism, the Nika rioters even burned churches. Yet, the rioters did not attack the Palace. Since the Imperial Guard was content to hide in the barracks and avoid any dangerous exertions such as defending the city, the rioters respected the army’s privacy.

Reveling in their power the rioters now proposed a new emperor, a reluctant but pliant noble named Hypatius. The “old” emperor was free to flee the city: the rioters had left him unimpeded access to the port. Indeed, Justinian was about to take that itinerary. He had called an imperial council of his few remaining supporters to plan the evacuation. However, this ignominious flight was scorned by the Empress Theodora.

Still very much the actress, she declaimed, “For one who has been an emperor it is unendurable to be a fugitive. May I never be separated from this purple, and may I not live that day on which those who meet me shall not address me as mistress. If, now, it is your wish to save yourself, O Emperor, there is no difficulty. For we have much money, and there is the sea, here the boats. However consider whether it will not come about after you have been saved that you would gladly exchange that safety for death. For as for myself, I approve a certain ancient saying that royalty is a good burial-shroud.”

If the Empress was prepared to fight and die for the throne, the men of the court were shamed into being just as heroic. (The court eunuchs probably were still eager to leave.) Although the Imperial army was unreliable, several of the loyal officers had personal retainers who would follow orders. These troops numbered no more than a thousand, but they were an elite force of veterans. The rioters were in the tens of thousands but they were an undisciplined mob and, worse for them, oblivious to the danger. The Nika rioters had gathered at the Hippodrome, the social center of the city. It was a great place for a celebration but an even better place for a massacre.

The Hippodrome’s entrances were all at one end of the stadium. The troops seized the gates and then proceeded to scythe the trapped mob. Thirty thousand were killed; the Nika Riot was crushed. The hapless Hypatius was captured. He pleaded his innocence and Justinian believed him; however, Theodora still insisted on an execution.

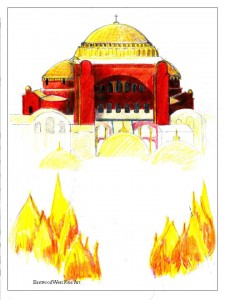

As for Justinian, he did not view the riots as a warning but rather as an opportunity. First, he would have to raise even more taxes to rebuild the city. More importantly, Constantinople now would be rebuilt his way. For example, the rioters had destroyed the old church of Hagia Sophia. Justinian envisioned the new church to be a monument to him.

And it still is.