January 25th:

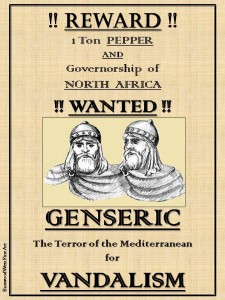

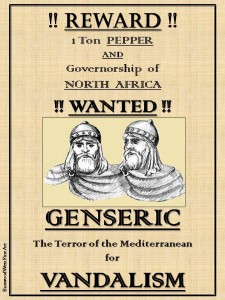

If “Only the good die young,” that would explain Genseric’s long life. He died this day in 477 at the age of 87 or so. We are not quite sure of his actual birthday; being the illegitimate son of a chieftain of a minor barbarian tribe, who noticed? His departure was more conspicuous. After all, by that time he was the King of North Africa, the terror of what was left of the Roman world, and the scourge of the Church. Even today, his legacy lingers. Through his deeds, his tribe is remembered as a felony: Vandal.

If “Only the good die young,” that would explain Genseric’s long life. He died this day in 477 at the age of 87 or so. We are not quite sure of his actual birthday; being the illegitimate son of a chieftain of a minor barbarian tribe, who noticed? His departure was more conspicuous. After all, by that time he was the King of North Africa, the terror of what was left of the Roman world, and the scourge of the Church. Even today, his legacy lingers. Through his deeds, his tribe is remembered as a felony: Vandal.

Genseric’s career would make a suitable case study for any MBA program. If anyone deserved to be named Entrepreneur of the Fifth Century, it certainly was him. Of course, the early fifth century was a great time to be a barbarian. The Rhine River was all the defense that the Roman Empire had in the West, and it was hardly impassable. (The Germanic tribes waded into the Empire or–to use the Latin pronunciation– in-vade.)

Most of the tribes were competing with one another as to who would loot Gaul. The Vandals, led by Genseric and his annoyingly legitimate half-brother Gunderic, decided to avoid the mob and a losing battle by moving on to Iberia. They were among the first German tourists there. Unfortunately for the Vandals, the Visigoths also heard about Hispania and migrated there, too. Preferring to be the sole barbarians on the peninsula, the Visigoths began wiping out the Vandals. Half of the tribe was gone, Gunderic was dead, and Genseric was now the king of this sorry remnant; in 429, however, the Roman governor of North Africa saved the Vandals. The governor was rebelling against the Emperor and needed mercenaries, so he transported the entire tribe to North Africa.

Ironically, the Roman governor called off his rebellion, but the Vandals didn’t. Genseric liked North Africa; in those days the land was fertile and had not become yet an extension of the Sahara. Prosperous provinces but with meager defenses–what more could Genseric ask! Within ten years, the Vandals occupied the territory extending from Libya to Morocco. (Yes, Rommel’s Afrika Korps was actually the second German invasion there, and the less successful of the two.) Carthage, the capital of Roman North Africa surrendered without a fight; the Vandals occupied the city while most of the populace was at the chariot races.

Genseric’s next venture was piracy. The Vandals proved quite adaptive and quickly developed a fleet that terrorized the western Mediterranean. They conquered the islands of Sicily, Sardinia and Corsica. What could Rome do but flatter him. In 442 the Emperor Valentinian III recognized Genseric as the King of everything he had seized; the official title was supposed to make him behave with regal decorum. Genseric would be further placated by a marriage into the imperial family. The Emperor’s three-year-old daughter was betrothed to Genseric’s oldest (and adult) son; it would be a long engagement. So for the next 13 years Genseric seemed content to administer his realm, restoring to North Africa the stability and prosperity that the disintegrating Roman Empire had failed to maintain. He did tax the patrician landowners and the Catholic clergy (who usually were one and the same) but most of the populace found Vandal rule an improvement.

And Genseric was bored! Although now was in his sixties, he definitely had not mellowed. Yet he felt constrained by his treaty with Valentinian III and the western half of the Roman Empire. True, he was free to attack the Byzantines or his old enemies the Visigoths, but they had the inconvenient capacity to defend themselves; and Genseric really did not like fair fights. However, the life expectancy of a Roman Emperor was rarely long, and Valentinian III made enemies. He was assassinated in March, 455, and two months later Genseric was at the gates of Rome, proclaiming himself the avenger of Valentinian and the protector of his family.

For all his lofty proclamations, his basic demands were “give us everything and no one will be hurt”. Two years earlier, Pope Leo I had persuaded Attila the Hun not to sack Rome; the Pope would not find Genseric to be such a softie. The Visigoths in 410 had sacked Rome, indulging in murder, rape and pillage; but they had refrained from looting churches. The Vandals lacked that sense of etiquette; of course, after the Visigoths, Rome had little left to loot except the churches. Genseric’s sack was bloodless and platonic, but his irrreverent attitude to church property would earn the Vandals their lasting infamy. The medieval monk chroniclers would not forgive the Vandals’ transgression, and their animosity became our perception: VANDALS!. Although usually left to the victor, history is always written by the literate.

Furthermore, despite his agreement with the Pope, Genseric did not strictly observe his pledge of good behavior. Apparently kidnapping was still permissible. No, Genseric was not tacky enough to seize the Pope; but he did take the widow and two daughters of the late emperor. The dowager empress was a Byzantine princess, so Constantinople would be sent the ransom note. Genseric was only offering the widow and one daughter; the other–now nubile–girl was going to marry his son. The ransom negotiations lasted six years. In that time, the Byzantines were hoping that Genseric would succumb to enemies or old age. Both were reasonable expectations but he proved equally adapt at outfoxing his foes and time itself.

In 468, the Byzantines amassed an overwhelming force to crush the Vandal kingdom. More than 1100 ships, with 100,000 soldiers, ascended on Carthage. Unfortunately, the Byzantine emperor appointed his brother-in-law the commander. Genseric offered to surrender and, while the peace terms were being negotiated, the Vandals attacked the lulled Byzantines. Half of their fleet was lost. The idiot brother-in-law returned to Constantinople where he sheltered in a church until the emperor agreed only to exile him.

And the 80 year-old Genseric would outlast another two Byzantine emperors, five Roman emperors and the Western Empire itself. But his kingdom would only survive him by 57 years; he had left his sons an empire but none of the vision or the abilities to preserve it.