Die Polar Disorder

Posted in On This Day on March 29th, 2009 by Eugene Finerman – 2 CommentsMarch 29th

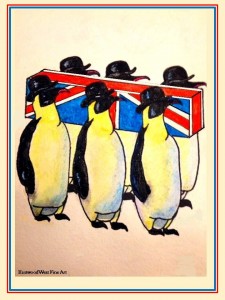

On this day in 1912, Robert Falcon Scott ended a rather disappointing trip to Antarctica. Nature evidently did not show the proper respect to a representative of the British Empire. The penguins did not greet his expedition with a few choruses from Gilbert & Sullivan, and the South Pole proved rudely aloof. Indeed, if the Pole had any sense of deference, it would have come to him.

On this day in 1912, Robert Falcon Scott ended a rather disappointing trip to Antarctica. Nature evidently did not show the proper respect to a representative of the British Empire. The penguins did not greet his expedition with a few choruses from Gilbert & Sullivan, and the South Pole proved rudely aloof. Indeed, if the Pole had any sense of deference, it would have come to him.

Expecting to be the first gentleman to reach the South Pole, Captain Scott planned a grand tour, with modern conveniences as well as traditional fashions. His expedition included motorized sleds and horses, so he had a choice in how he would ride to the South Pole. Had he personally selected the dog teams, they probably would have been comprised of pugs.

The expedition promised to be an extravaganza. In addition to the complete catalog from Harrod’s, Scott’s team included a staff of scientists who would provide suitably British names for any discovered species, landmarks and eclectic oddities. Of course, the undertaking would be costly, and His Majesty’s government would only subsidize some of the expenses. Scott actually had some ability as a fundraiser, and found a number of private contributors. Fortunately, in the Edwardian era sponsors were more discreet, so Scott was not obliged to wear a parka covered with corporate decals. (However, you can imagine what Lipton would have paid to be the first tea brewed at the South Pole.)

The expedition arrived in Antarctica in early 1911 and spent the better part of the year preparing for the trip to the South Pole. For lack of Lyons restaurants along the route, food depots were established at some distances from the base camp to accommodate the polar tourists. The motorized vehicles and horses were thoroughly tested and found to be thoroughly inadequate. Neither could withstand the cold. The dog teams proved more resilient, but Scott had more faith in his own bipedal resolve. He and four members of his expedition would walk to the South Pole, dragging supply sleds with them.

After a two month hike, they arrived at the South Pole on January 17, 1912 only to discover that it already was the Norwegian consulate in Antarctica. Roald Amundsen had arrived there a month earlier, using dog sleds. It may have been summer in Antarctica, but Scott and his team were suffering from frostbite, dehydration and hunger. (Amundsen had relied on dogs for both transportation and–when necessary–an entree.) Depressed and malnourished, Scott’s crew became unlucky and careless. On the trek back, one Briton suffered a fatal injury, and no one could quite remember the exact location of the food depots. They actually were quite close to one of the food caches when, on March 29th, Scott and his team starved and froze to death.

Search teams from the base camp found the bodies, along with Scott’s diary. The diary, after careful editing to remove any hint of incompetence, was published as an epic of British heroism.

Of course, his heroism would have been unalloyed if Scott had the least idea what he was doing.