On This Day in 1915

Posted in General, On This Day on May 7th, 2009 by Eugene Finerman – 2 CommentsMay 7th

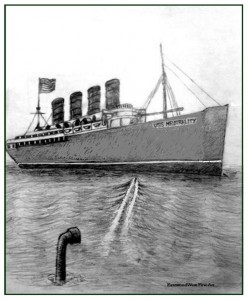

On May 7, 1915, U-boat Kommandant Walther Schwieger had to make a difficult choice. Would he want 4,200,000 rifle bullets to reach his English enemies or would he prefer 100,000,000 Americans to join the war against Germany. Deciding that the bullets were a more immediate danger, Schwieger sank the ocean liner transporting the bullets–along with 1900 passengers and crew. The ship was the Lusitania.

On May 7, 1915, U-boat Kommandant Walther Schwieger had to make a difficult choice. Would he want 4,200,000 rifle bullets to reach his English enemies or would he prefer 100,000,000 Americans to join the war against Germany. Deciding that the bullets were a more immediate danger, Schwieger sank the ocean liner transporting the bullets–along with 1900 passengers and crew. The ship was the Lusitania.

One torpedo was sufficient to sink the British ship. Even Schwieger admitted that it was a lucky shot. The Lusitania sank in only 18 minutes. It took even less time for 1198 people to drown. The victims included 128 Americans. Schwieger also succeeded in sinking any neutrality in American public opinion.

Up until that time the Americans dismissed the Great War as just as another elaborate, convoluted European opera except that the main characters really were trying to kill each other. The public consensus had no preferences. Yes, Kaiser Wilhelm did seem repellent but so did the British Empire. Just ask the large number of Irish-Americans. Among the growing Jewish population in America, Tsar Nicholas II was not fondly remembered; pogroms rarely are. Furthermore, many Americans were of German descent and felt a certain nostalgia for the Vaterland; they had no wish to see their new country fight their old one.

The sinking of the Lusitania ended America’s indifference. Popular sympathy was now with the Allies, and many were ready to act on that sentiment: fight the Hun! Responding to America’s outrage, the Germans attempted to justify the sinking of Lusitania by offering desiccated legalese. The German government had publicly announced its policy of unrestricted submarine warfare against any enemy shipping; it had placed ads in American newspapers! Obviously, the passengers of the Lusitania should have known better. The Teutonic jurisprudence did not satisfy the public outrage. Indeed, within a few months the German government decided to refrain from sinking passenger ships. (In the meantime, Lieutenant Schwieger sank the R.M.S. Hesperian–a hospital ship; the Second Reich did have some standards and apologized for that.)

America was ready for war, but President Wilson was not. He had two reservations. The first was political: he wanted to be reelected in 1916 and he couldn’t be sure how all those Irish-American Democrats would feel about a military alliance with Britain. (The American Jews would be placated and gratified by the appointment of Louis Brandeis to the Supreme Court, and the German-Americans tended to vote Republican anyway.) His second reservation was philosophical, and our only Ph.D. President took his philosophy very seriously. If America was to go to war, there had to be a nobler reason than revenge for the Lusitania or a visceral dislike of the Kaiser and German brutality. America needed an aspiration to justify war. If this were a war between democracy and autocracy, then Wilson would have committed our nation to the fight. But the Allies included Tsarist Russia–a tyranny far more repressive than Germany. While the Tsar reigned, President Wilson would maintain America’s neutrality.

But the Tsar fell in March, 1917 and Woodrow Wilson declared war on Germany the next month. The American victims on the Lusitania at last would be avenged.

As for Lieutenant Schwieger, in 1917 he finally had the misfortune to confront an armed ship. Attempting to flee, he piloted his U-boat into a minefield. In his last moments, he knew what it was like to be on the Lusitania.