September 10, 210 B.C.: The Emperor Qin Shi Huang died…but for how long?

How would you react if I said that George Washington was a vampire, Charlemagne a demon and Peter the Great an extra-terrestrial? You would think that I was joking or psychotic (although the two are not mutually exclusive). But what if I made all those aspersions against Qin Shi Huang, the first Emperor of China? You could say, “Yes, I saw that in a movie.” He has been a featured villain in “My Date With a Vampire” and “Stargate.” A computer-animated version of him recently threatened mankind in “The Mummy: Tomb of the Dragon Emperor.” Don’t worry, Brendan Fraser saved you.

So why does Hollywood and the West so hate this Chinese leader who forged feuding states into a great empire, unified his realm with a common language, and built the Great Wall as well as that fabulous tomb with a life-sized terra cotta army to guard him in the afterlife? Actually, we don’t. From our perspective, he was so cool that we named the country for him. Yes, the western pronunciation (equal parts error and arrogance) used to say “Chin” instead of the correct Qin. We now know better although we have to yet call the country Qina.

He was born in 259 BC and with the less exalted name of Ying Zheng; Qin Shi Huang was a title he would bestow upon himself . At the time, there was no China but rather seven vying kingdoms. Qin was one of these kingdoms, and considered a rather backward state. If dismissed as a barbarian, Ying Zheng embraced the role. Ascending at the age of 13 to the throne, Zheng made war his study and policy. His army was better-armed and trained than his rivals, and he eschewed the etiquette that had governed warfare among the kingdoms. Traditional war had been waged as a ritualized mass duel. Zheng did not believe in a fair fight; he preferred to be a victorious barbarian than a dead gentleman. In 221 B.C., by the time he was 38, he had conquered the other six kingdoms. With no modesty but complete accuracy, he proclaimed himself the First Emperor of Qin: Qin Shi Huang.

There had been Chinese emperors before him, but they were kings with more pretense than power, asserting a degree of precedence over the other rulers. But Qin Shi Huang was the real–and unrivaled–sovereign of an empire, and he was going to rule every bit of it. To govern over this large and diverse realm, he established a centralized bureaucracy. The empire was divided into provinces, the provinces into prefectures; the corps of administrators had limited powers, sufficient to do the emperor’s will but not challenge it. The former kingdoms were to be integrated into one. Where there had seven different systems of weights and measures, there now would only be one uniform system. Where there had been seven different dialects, now there would be just one language unifying the educated of China. Of course, the peasants could maintain their idiomatic garble, so long as they obeyed commands in the official Chinese. In fact, Qin Shi Huang had a project for them. In the north, nomadic tribes threatened China, and the Emperor did not like any barbarians but himself. He assigned 300,000 laborers to build a wall along the northern border. I don’t think that particular wall needs a formal introduction.

The Emperor died in 210 B.C.. His tomb, surrounded by 8000 terra cotta warriors, now commands the tribute of the world’s tourists. Unfortunately, the emperor’s heirs seemed unnaturally eager for their own tombs. They proceeded to kill off each other without gaining control of the empire. The provinces revolted and China collapsed into 18 kingdoms. The last of Shi Huang’s dynasty abdicated in 207 B.C., hoping to avoid execution. He only delayed it for a year, but his captor was to establish a dynasty that would last four centuries: the Han. While Qin rule may have lasted scarely 20 years, the example of Shi Huang has been followed for 2000 years. The subsequent imperial dynasties would reestablish Shi Huang’s empire and most of his methods.

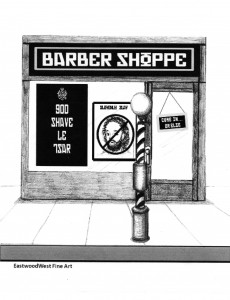

So how did Qin Shi Huang acquire the diabolical reputation that Hollywood loves to exploit? However forceful and dynamic we might think him, the Chinese intellectuals hated him. History, while often written by the victor, is always written by the literate. These Chinese intellectuals condemn the Emperor for suppressing the teachings and writings of Confucius. Shi Huang’s new empire had no place for the values and ideas of the old kingdoms; he regarded their contemplative nature and reverence for tradition as weaknesses. The writings of Confucius were burned; on a number of occasions, so were Confucian scholars. The suppression was so relentless that only incomplete works of Confucius now survive. Of course, subsequent generations of Chinese scholars revered Confucius and so they reviled Shi Huang, condemning him for what he actually did as well anything they could imagine.

Their version of the Emperor was of shameful birth, the son of a pregnant concubine foisted upon a naive king. And that duplicitous start was the portent of an evil life. A demon in human form, he immersed himself in the black arts, aspiring to immortality. (Given the quality of his heirs, an immortal emperor would have been preferable.) According to one tale, Shi Huang took doses of mercury to attain eternal life. Well, mercury certainly would stop him from getting any older. He was all of 50 when he took up residence in his palatial tomb.

But could such a fiend stay dead? He is still plotting crimes and avoiding assassination in Chinese films, and Hollywood certainly keeps his supernational version vicariously alive. But has China actually seen the return of the ruthless, dynamic, perhaps even charismatic tyrant? Mao Zedong seems a likely reincarnation.