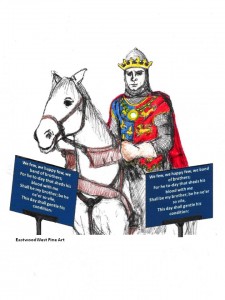

St. Corporate Day

Posted in General, On This Day on October 25th, 2013 by Eugene Finerman – 3 CommentsOctober 25, 1415: The Battle of Agincourt

On this day in 1415, a beleaguered CEO offered these team-building thoughts to his “stakeholders”:

On this day in 1415, a beleaguered CEO offered these team-building thoughts to his “stakeholders”:

We few, we happy few, we band of brothers;

For he today that sheds his blood with me

Shall be my brother …

Stirred by such speech, you too might well overlook the fact that your newfound brother makes 300 times more than you, and that he is the buffoon who put you in such a desperate plight.

In fact, the battle of Agincourt was decided by French incompetence, not English poetry. Outnumbering the English by approximately three-to-one, the French could have used any number of tactics to win the campaign: flanking, envelopment, siege….There was only one possible way that the French could have lost the battle of Agincourt. That would be a full-frontal cavalry assault in constricted terrain, leading to an impassable traffic jam of horses and easy shooting for English archers.

Of course, who would be that stupid? Oh, oui.

However, I will concede that Henry V could not have made that glorious St. Crispin’s Day speech. First, it would have been in Middle English–which no one ever understood. Furthermore, the speech–in that form–would never have survived the departmental approval procedure. Before delivering the St. Crispin’s speech, Henry–or his speechwriter–was required to submit a draft to the legal department and human resources.

In 1415, that editorial inquisition was in the hands of Lord Chancellor Beaufort and the King’s brother, the Duke of Bedford.

Beaufort: “We few, we happy few…” Too many pronouns, too many adjectives. “We” is too vague a term, too easy to misinterpret. A positive and specific identification is necessary, if only to avoid trademark disputes in future treaties. “Few” has a negative context, as if the English army were conceding an inadequate number for this campaign. If Henry survives the battle, he would never survive the litigation. Come up with a more positive description of our army’s size.

Bedford: And “Happy”? Really, that is unprofessional and inappropriate to a war. If we must have an adjective, let’s make it a serious one. And “band of brothers?” I am the king’s brother and I have no idea what that means. Is he promising everyone can be a duke like me?

Beaufort: Carried away by alliteration, completely irresponsible. There has to be a concise and practical definition of the relationship between the king and his soldiers.

Bedford: “For he today that sheds his blood with me

Shall be my brother …”

Is he criticizing our healthcare policy? We certainly do cover wounds–at least battle-related ones–and the men will receive appropriate bandages rather than this unsolicited affection. You know, that could actually be viewed as a form of harassment….

So, on October 25, 1415, Henry V assured his beleaguered men:

“This adequately numbered English army, this proactive English army

This armed association

For anyone who, in this specific time period, should acquire a work-related decoagulating condition

Would be entitled to appropriate coverage from this association.”

And if Henry said anything more, no one was listening.