January 20, 1265: The First Meeting of “Talking Place” (You know it might sound better in French)

In 1215, rebelling against the repressive rule of King John, the barons of England forced the cowed monarch to sign the Magna Carta, a charter of concessions defining and restricting his power. Henceforth, the King could no longer arbitrarily arrest an Englishman or seize his property. Neither John nor any other English king would again be a tyrant. However, the Magna Carta did not guarantee the king’s competence. The monarch was still free to be weak, inept and reckless; and Henry III–the son of John–fully exercised those dubious prerogatives. In 1264, the barons rebelled again, now to impose some restraining responsibilities on the bankrupt Crown. And the rebels’ leader Simon de Montfort had a remarkable idea to accomplish that: a governing council with elected representatives.

In 1215, rebelling against the repressive rule of King John, the barons of England forced the cowed monarch to sign the Magna Carta, a charter of concessions defining and restricting his power. Henceforth, the King could no longer arbitrarily arrest an Englishman or seize his property. Neither John nor any other English king would again be a tyrant. However, the Magna Carta did not guarantee the king’s competence. The monarch was still free to be weak, inept and reckless; and Henry III–the son of John–fully exercised those dubious prerogatives. In 1264, the barons rebelled again, now to impose some restraining responsibilities on the bankrupt Crown. And the rebels’ leader Simon de Montfort had a remarkable idea to accomplish that: a governing council with elected representatives.

Ironically, the pioneer of parliamentary government had nothing liberal in his pedigree or upbringing. Simon de Montfort was an aristocrat, the son of a warlord who had made a fortune in the Crusades. Nor was Simon even English, but French. France, however, afforded him few opportunities; his older brother would inherit the family estates. But he did have a tenuous claim to an English title. The last Earl of Leicester had died childless, and Simon was his great-nephew. So in 1230 the 22 year-old Frenchman travelled to England to become an Earl.

Thirteenth century England was a feudal society. The King and two hundred nobles ruled four million people. There were some 80 boroughs, their term for cities and towns; London was the largest–with a population of approximately 30,000. Most of the English–at least 80 percent–were peasants. Half of that number were serfs, little more than human livestock. The ruling class and their subjects barely spoke the same language. The French of the aristocracy and the Angle-Saxon of the commoners were gradually evolving into a mutually understood language: Middle English. And on the English throne was the affable catastrophe Henry III.

Simon de Montfort was not the only fortune-hunter at the English court, and most of them were French, too. The king had many Gallic relatives and they all made themselves his guests. But Simon, with his soldier’s bearing, stood apart from the fawning courtiers. Henry was impressed and so granted Simon part of the Leicester inheritance. Montfort could have the lands and income of the earldom but not the actual title. That would have to be earned. The King expected military service, but Simon chose a different type of campaign. Eleanor Plantagenet was an attractive, young woman; she was also the king’s sister. Simon married her, and Henry’s wedding present was the Earldom.

In his rise to prominence and power, the Earl of Leicester earned the envy and enmity of other courtiers. The King could be easily swayed by malicious reports, and so Simon often found himself the victim of the royal whimsy. Although he had certainly proved himself adept at court politics, Simon loathed it. He fled the sordid intrigues by going on a crusade in 1240. At least in the Middle East, his enemies were clearly defined and usually more honorable than English courtiers. He returned to England and the politics a year later, but would always speak longingly of the Crusades and their moral clarity.

When the King summoned the Royal Council, an assembly of England’s leading nobles and prelates, it was sometimes for their advice but usually for their money. The Magna Carta forbid the King from raising taxes without the Council’s consent. Of course, the Earl of Leicester was a member of the Royal Council. He had first been a staunch supporter of the King; that might be expected of a rising courtier and a brother-in-law. Overtime, however, experience and disillusionment turned him into a critic of the King. Henry’s rule was an appalling farce. Royal offices were doled out to corrupt, incompetent favorites. Wars were lost through cowardice and mismanagement. The King bankrupted the treasury pursuing ridiculous schemes; one was a campaign to win the crown of Sicily. And, in 1258, when the King wanted more money for this Sicilian fiasco, the Council not only refused but, led by Simon de Montfort, demanded constraints upon Henry and the reform of the government.

The outraged nobles could not be ignored. Each one had a personal army and their combined might could overwhelm the King’s forces. Intimidated, Henry agreed to abide by whatever reforms would be determined by a special session of the Royal Council. Representatives of the King and the Barons met at Oxford to create a program of reforms. They intended to limit the king’s power and to impose on government officials a standard of ethics and competence. Their proposals are now remembered as the “Provisions of Oxford.”

According to the Provisions, the King would be under the supervision of a 15- member governing council called a “parliament.” “There are to be three parliaments a year…To these three parliaments the chosen counselors of the King shall come, even if they are not summoned, in order to examine the state of the kingdom and to consider the commons needs of the kingdom and likewise of the King.” Note that the parliament would meet, regardless of Henry’s approval. The Provisions also imposed term limits of one year on all royal appointees, and these appointees would have to report to the parliament.

Henry agreed to the Provisions in October, 1158 and then spent the next two years stalling on their implementation. All the while, Henry was corresponding with the Pope, pleading for the Church to absolve him from his pledge. In April, 1261, the Pope did, and now Henry could sanctimoniously reject the reforms. However, the Church had not threatened to excommunicate Simon de Montfort and the Barons; so they could still demand the Provisions. With England verging on Civil War, Henry offered another proposal. King Louis IX of France was renowned for his sense of justice; why not let him arbitrate the dispute. Montfort agreed, putting his faith in the eventual Saint Louis. On this earth, however, Louis was still very much a king, and he was not going to undermine the principles of monarchy. In January, 1264 he decided in Henry’s favor.

The nobles had been outmanuevered but not pacified. They had no alternative but war; but they had no better leader than Simon de Montfort. He was 56 years old, an old man in those times, but still eager to lead this crusade. King Henry and his son Edward were gathering their forces at Lewes, in Southeastern England. Montfort had a smaller army but he knew Henry’s incompetence and Edward’s inexperience. The Earl attacked; by the end of the day, Henry and Edward were prisoners and Simon de Montfort was “the uncrowned king of England.” Henry would remain king, if only in name. The actual power would be in the hands of a triumvirate of regents: Montfort, of course, and his allies the Bishop of Chicester and the Earl of Gloucester.

But Montfort knew that this arrangement was expedient and temporary. There had to be a sound and lasting basis for responsible government. Both the Provisions’ proposed parliament and the Royal Council had been an assembly of aristocrats. Montfort wanted a parliament that drew upon the advice and consent of the commoners. So, he would convene a parliament in January 1265, and he ordered the 37 counties and some 80 towns of England to send elected representatives. It was unprecedented, and many of Montfort’s fellow barons were appalled. Some, including the Earl of Gloucester, would now conspire to restore the King. What happened at Montfort’s parliament? Ironically, we do not know the details of this momentous event. No records have survived. Montfort’s enemies might have destroyed them.

Those enemies were gathering strength. With the help of the treacherous Gloucester, Prince Edward had escaped and now was rallying an army in the west of England. Montfort led an army in pursuit, bringing along Henry as hostage. The Earl camped at Evesham and awaited reinforcements. They never came. Prince Edward, proving himself a bold and capable commander, had destroyed that force and now would surprise Montfort. The Earl was killed, and his body mutilated, its parts sent throughout the kingdom as trophies. King Henry was released from one captivity but placed in another. The real ruler would be Prince Edward. Ironically, Edward was exactly what the defeated Barons had wanted in a king: strong, efficient, and responsible.

He would also prove a statesman. When King Edward I summoned a parliament in 1275, he ordered the counties and towns of England to send elected representatives. A wise king would want the support and the advice of the commoners. So Montfort’s radical idea became the precedent of parliament, and the basis of representative government. Today, a descendant of Edward sits on the British throne, but the heirs of Simon de Montfort–the elected members of Parliament –rule Britain.

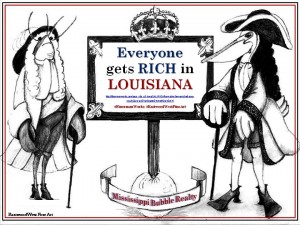

Wall Street did not pioneer the stock market crash. No, that distinction belongs to France some 70 years before there was a New York Stock Exchange. Yet, in a way the Crash of 1720 was America’s fault. All those French investors were absolutely certain that there were gold mines in Louisiana, and that fortune was just waiting for them. They had been assured of it by that widely-acknowledged financial genius John Law.

Wall Street did not pioneer the stock market crash. No, that distinction belongs to France some 70 years before there was a New York Stock Exchange. Yet, in a way the Crash of 1720 was America’s fault. All those French investors were absolutely certain that there were gold mines in Louisiana, and that fortune was just waiting for them. They had been assured of it by that widely-acknowledged financial genius John Law.